History

Mythic Origins

Kambô is said to be named after the legendary pajé (medicine man) Kampu. According to Kaxinawá tradition, Kampu learned of the medicine from a forest spirit after exhausting all other means to heal his tribe. The spirit gave him a vision of the frog and showed him how to use its white secretion for healing.

Returning to his people, Kampu cured the tribe and became known as Pajé Kampu. After his passing, his spirit remained in the giant monkey frog, continuing to protect the health of those who defend the forest. Among indigenous peoples, the secretion became known as Kambô, although some tribes call it Sapo, Kampu, or Vacina da Floresta.

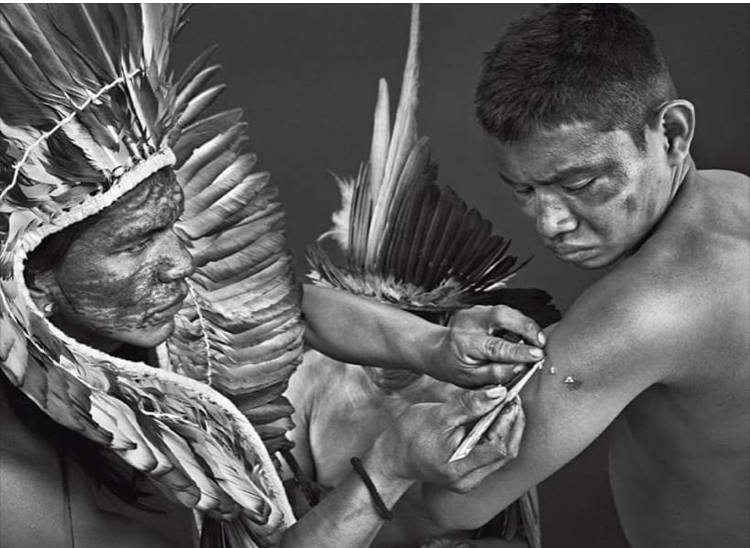

Indigenous Use

Today, the secretion is still used widely among indigenous Pano-speaking groups—including the Katukina, Asháninka, Yaminawá, and Matsés (Mayoruna). Some believe that even the classical Maya knew of Kambô, as tree frogs appear in their artistic depictions alongside mushrooms.

Traditional applications include cleansing toxins, enhancing strength and stamina, aiding in fertility or inducing abortion, and dispelling panema—negative energy that brings misfortune. In the rainforest, Kambô is used in hunting to reduce food and water needs, minimize scent, and imbue the hunter with a rumored “green glow” that draws prey closer.

Western Encounters

The first Westerner to document Kambô was French missionary Constantin Tastevin, who stayed with the Kaxinawá in 1925. His informants claimed the self-envenomation ritual originated with the Yaminawá.

In the 1980s, journalist Peter Gorman (author of a book Sapo in My Soul) and anthropologist Katharine Milton lived among the Matsés/Mayoruna and brought Kambô samples to biochemists John Daly and Vittorio Erspamer, whose peptide analysis revealed significant pharmacological potential. Pharmaceutical attempts to synthetically reproduce Kambô peptides have largely been unsuccessful.

Modern Applications and Legal Response

Until the 1990s, Kambô was rarely applied outside indigenous communities. In 1994, Francisco Gomes, a half-Katukina caboclo in São Paulo, began offering it as therapy. From 1999, others—including holistic practitioners and members of religious traditions such as União do Vegetal and Santo Daime—began offering Kambô more broadly.

In response to growing commercial interest, the Brazilian government banned all advertising of Kambô’s therapeutic benefits in 2004—a move partly aimed at protecting indigenous knowledge. Despite this, Kambô’s global presence has grown, rooted in ceremony, tradition, and ethical training protocols.

In the 2000s, Kambô began reaching non-indigenous practitioners. A key figure in this shift was Master Practitioner Karen Kanya-Darke, who founded the International Association of Kambo Practitioners (IAKP). The IAKP is the world’s first formal training body for Kambô, committed to safe, responsible, ethical, and sustainable use of the medicine, with a deep respect for its Amazonian origins [1].

The association offers tiered training—including Basic, Advanced, Teacher training, and a mentoring program for Master Practitioners—across locations in Europe, North America, Latin America, and Asia [2]. Students learn ancestral application techniques, modern safety standards, and ceremony protocols grounded in tradition and integrity. The IAKP pioneered methods such as the 3×3 warrior initiation, layered and chakra point treatments, and the use of test-points to assess client sensitivity safely [3].